Brooks Macdonald on Behavioural Investing

By Andrew Prosser, Investment Office, Brooks Macdonald

Click here to download article

Many people think of investing as being a rational, logical process. However, investment decisions are subject to the biases and emotions of the people making them. It is therefore important for investors to be aware of their preconceptions, in order to better understand how they can affect their decision making.

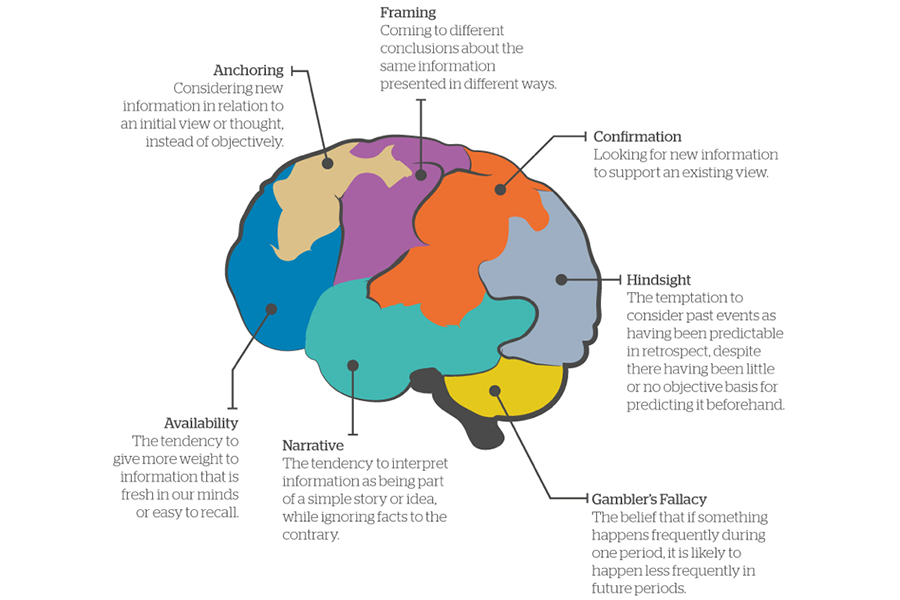

There are a huge number of biases that can be detrimental to investors’ decision making processes, but these can generally be grouped under one of two different headings. Firstly, cognitive biases are those which arise because of a lack of knowledge, poor information processing or memory errors.

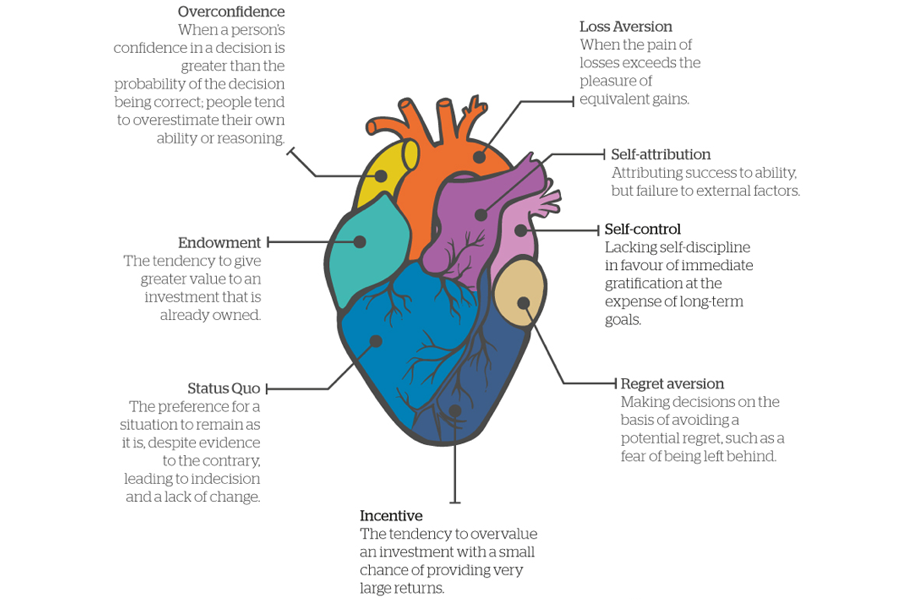

Secondly, emotional biases are those which are the result of an investor’s feelings, impulses or intuition:

These behavioural biases can cause investors to make mistakes, but because of this they also create market inefficiencies from which others can profit. Although this list is by no means exhaustive, it highlights some of the common mistakes behavioural biases can cause:

- Holding on to losing stocks too long, or selling winners too early.

- Trading too frequently and getting caught up in day-to-day ‘noise’.

- Becoming emotionally attached to an investment case and failing to incorporate new negative developments.

- Making too many speculative investments in the hope of large pay-offs.

- Being overly cautious due to fear of suffering losses.

- Not being aware of the limitations of research.

- Not differentiating between luck and skill.

How can biases be avoided?

While it is impossible to fully eliminate certain biases, there are steps that can be taken to minimise their effects. First, it is important to acknowledge biases so they can be corrected. Next, investors should establish a clear and well thought out investment philosophy, as well as robust processes that they can use to apply it. The following provide some specific steps investors can take:

- Set realistic expectations about the returns your investments are likely to generate.

- Conduct thorough investment research and evaluate subsequent developments objectively.

- Take a long-term investment approach and avoid reacting to market noise.

- Actively seek out contradictory views, data and conclusions.

- Create simple rules to avoid emotional attachments and stick to them.

- Differentiate between luck and skill. The fact that markets tend to rise makes it easy to become overconfident.

- Pay as much attention to mistakes as successes; learning from mistakes is more difficult, but can also be more valuable

1) Availability bias: The tendency to give more weight to information that is fresh in our minds or easy to recall.

Example: People tend to overestimate the likelihood of plane crashes because they are heavily publicised and therefore stick in our minds. However, the odds are actually very low, at around 1 in 11 million.

Implication: An example of availability bias relates to the fear of all-time highs. As equity-market crashes have historically occurred at times when markets have been at all-time highs (for example, before the Dotcom and Sub-Prime crashes in 2000 and 2008, respectively), investors tend to associate the phrase “all-time highs” with the bursting of asset bubbles. However, it is far more common for markets at all-time highs to carry on rising. In fact, all-time highs are a common occurrence. Since 1927, the S&P 500 Index has closed at new all-time high around 1,100 times, roughly once in every 19 trading days.

2) Anchoring effect: The tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information offered.

Example: Opening offers have a strong effect in price negotiations, typically serving as anchors that influence the subsequent discussions. Prices lower than the initial price seem more reasonable, even if they are still higher than what the item is really worth, and vice versa.

Implication: A common trap is investing in stocks just because they have suffered large price drops, without sound fundamental basis. Previous high prices cause investors to believe the stock now represents good value; however, share-price declines often represent deteriorating company fundamentals. By employing a robust, ongoing investment process, investors can mitigate the impact of the anchoring effect on their portfolios.

3) Framing: Coming to different conclusions about the same information presented in different ways.

Example: In a 2006 experiment on conference-goers, 93% of attendees registered early when a penalty fee for late registration was emphasised, but only 67% did so when the same terms were presented as a discount for early registration.

Implication: Studies show that risk-averse investors are more likely to invest in portfolios that are presented in terms of historical returns and volatility, rather than probability of losses. When choosing investments, it is important to focus on their underlying characteristics and not inconsequential cosmetic factors.

4) Confirmation bias: Looking for new information to support an existing view.

Example: A doctor with a hypothesis as to what disease a patient may have may then look for evidence that confirms that diagnosis, while overlooking evidence that would disprove it.

Implication: After buying a stock, investors often selectively remember positive articles or research notes about it, while ignoring negative news. It has also been shown that the stronger the opinion, the stronger the tendency to seek out confirmation and ignore disconfirming evidence. However, it is often more useful for investors to actively seek views which oppose their own, as this can help them avoid loss-making investments.

5) Hindsight bias: Overestimating what could have been known. It is the temptation, after an event has occurred, to see the event as having been predictable, despite there having been little or no objective basis for predicting it.

Example: In a 2002 experiment, subjects were provided details of a medical procedure and a randomly assigned patient outcome to interpret the level of malpractice by the doctors. Although doctors were described to have used exactly the same procedure, higher levels of malpractice were reported when patient outcomes were negative than when they were neutral.

Implication: “I saw the 2008 crisis coming all along!” Many professionals overestimate the success rate of their past decisions, as it is easy to overestimate how predictable an event was after it has occurred. This can cause investors to take too much risk in the belief that their historic decisions were better than their results demonstrate. It is important for investors to embed appropriate risk controls into their investment process to ensure that their portfolios do not suffer from hindsight bias.

6) Gambler’s fallacy: The belief that if a random occurrence happens frequently during a given period, it is likely to happen less frequently in future periods.

Example: After observing a long run of red on the roulette wheel, people can incorrectly believe that black is now a more likely outcome.

Implication: Investors can buy stocks that have decreased in value, in the belief that further declines are unlikely.

7) Narrative bias: The tendency to interpret information as being part of a story or idea, while ignoring facts to the contrary.

Example: Investors often have the desire to find meanings and patterns in events. Framing a complex event in terms of a simple story often makes it easier to understand. The human brain hates uncertainty, so when it is confronted with difficult questions it tends to search out easy answers in terms it can understand. We will often attribute a simple cause/effect relationship where none may exist.

Implication: Some investors can be persuaded to invest in new companies after reading articles about the company’s potential, without looking into the company’s accounts, competitors, or management. Narrative bias is often accompanied by the anchoring effect and confirmation bias.

Emotional Biases

1) Loss Aversion: When the pain of losses exceeds the pleasure of equivalent gains.

Example: Some investors feel pain from losses more acutely than they feel pleasure from gains. If such an investor is faced with realising a loss, they may take an irrational level of risk to try and reverse it. An often quoted ratio for this pain-to-pleasure ratio is 2:1; i.e. the pain investors feel from losses is twice as great as the pleasure they feel from gains.

- The implications of loss aversion can include:

- Holding on to losing investments to avoid the pain of realising a loss, even if the investment’s prospects are deteriorating.

- Trying to reverse losses by doubling down on loss-making investments.

- Selling appreciating investments too quickly to lock in small gains. It is often appropriate for investors to continue to hold profitable stocks, even if they have already generated large profits.

- Holding excessively conservative portfolios (e.g. heavily overweight bonds or cash).

- Withdrawing from the market altogether.

2) Overconfidence bias: When a person’s confidence in their decision exceeds the probability that the decision is correct; people tend to overestimate their own reasoning ability.

Example: Almost everyone believes that they are an above-average driver, but by definition only 50% of people can be. When students in the US were asked to compare their driving skills to other people, 93% of them put themselves in the top 50% of drivers. Teenagers are actually twice as likely to have accidents as motorists in their 30s, three times as likely as those in their 40s and six times as likely as those over 50.

Implication: Investors can become overconfident in their abilities due to early successes, which may be due to luck. Overconfidence can lead to excessive risk-taking and overtrading, both of which can be harmful to returns. This is why fund investors should employ robust investment selection processes to determine whether each fund’s past performance has been achieved through luck or skill, thereby helping to determine whether it is likely to produce strong returns in the future.

3) Self-attribution bias: When a person attributes their successes to their abilities, but their failures to external factors.

Example: When students pass exams, they generally believe it is because they studied hard. If they fail, they often attribute their failure to external factors such as a poor teacher, a headache on exam day, or other distracting conditions.

Implication: If a stock performs well, a stock picker who has invested in it will likely attribute their success to their own reasoning. However, if the stock performs badly, they may blame factors outside of their control. Studies have found that investors tend to credit successes to their own abilities, which leads them to become overconfident and overtrade, thereby adversely impacting their future performance. It is appropriate for investors to determine what has driven their past performance, so that they can adjust their investment processes if and where necessary.

4) Self-control bias: A lack of self-discipline, often involving the need for instant gratification at the expense of long-term goals.

Example: Prevalent in many areas in life, such as dieting and exercising, self control is also a significant issue in pension planning. Many individuals do not save enough for retirement, instead spending too much during their working years and forfeiting benefits that would otherwise be enjoyed in retirement.

Implication: Rather than sticking to well thought out, long-term strategies, investors are susceptible to overtrade as a result of short-term market noise, which often has a detrimental effect on their longer-term returns. Such tendencies are often exacerbated by sensationalised newsflow distributed by the financial media.

5) Endowment bias: Attributing greater value to things we already own or know.

Example: A famous study of the endowment effect involved participants being given a mug and then offered the chance to sell it or trade it for an alternative of equal value (a pen). The authors of the study found that the amount of compensation participants wanted for the mug once they had already been given it was approximately twice as high as the amount they were willing to pay to acquire it.

Implication: Investors can become emotionally attached to stocks. This can make them invest too heavily, or hold on to them for too long. Information is also subject to endowment bias, as people tend to overvalue information they have taken time and effort to acquire; this is one of the main causes of the anchoring effect.

Avoiding losses is a key element of successful investing and emotional stock attachments can therefore have a significant adverse impact on long-term returns. To quantify this, an investment that loses 75% of its value then needs to increase by 300% just to return to its starting value (i.e. generate an average return of 15% a year over 10 years).

6) Regret aversion: Making decisions on the basis of avoiding a potential regret, such as a fear of being left behind.

Example: During the Dotcom Bubble, many investment managers invested heavily in technology stocks because they were afraid of missing out on the gains being experienced by others, or underperforming the market; this was a clear demonstration of ‘herd mentality’. However, many of these investments made very little sense in fundamental terms and ultimately led to large losses when the bubble burst.

Implication: Investors tend to gravitate towards stocks that they have made money on in the past, while avoiding stocks that they have lost money on. In addition, stocks that have appreciated in value since a prior sale are associated with regret and avoided because of the missed opportunity of buying at a lower price. However, it is important to have a defined strategy and clear long-term goals; this will help avoid the prospect of making damaging short-term mistakes.

7) Status quo bias: The preference for a situation to remain as it is, despite evidence to the contrary, leading to indecision and lack of change.

Example: In politics, the incumbent office holder is more likely to claim an election victory over new entrants. This is demonstrated by the fact that over 80% of incumbents seeking re-election in the US House of Representatives have won it. While there are obviously additional factors that affect re-election rates, such as incumbents that feel unlikely to win declining to run, there is still a clear tendency for the public to prefer to preserve the status quo.

Implication: Investors tend to make too few changes to asset allocations. However, it is important to take a pragmatic approach to asset allocation, involving independent evaluation of the macroeconomic and investment backdrops. Such an approach can help counteract the effect of status quo bias on individual stock pickers.

Furthermore, individual investors may not update their investment profiles as they grow older, causing their portfolios to become too risky for their individual situations. As such, the process of suitability assessment should be ongoing.

8) Incentive bias: Incentive bias describes the power that rewards can have on human behaviour; for example, the tendency to overvalue an investment because of the belief that it has a chance of providing very high returns.

Example: In the run up to the US sub-prime housing crisis, large sums of capital were lent to borrowers with poor credit histories, limited assets and low incomes, in the hope that they would generate large returns. The process was exacerbated by financial engineering, which caused misunderstandings of the quality of loans being made. Ultimately, high levels of defaults caused the US housing market to crash, with well known, long-lasting repercussions.

Implication: Broadly speaking, incentive bias can cause investors, particularly retail investors, to pay too much for small growth stocks in the hope of very large returns and not enough for large blue-chip companies which can provide lower, stable returns. Investors should avoid this bias by incorporating specific qualitative and quantitative investment selection controls into their investment processes.

In terms of individual companies, investors should also ensure that management incentives are aligned with those of shareholders.

Important information

This article is intended for professional advisers only and is not intended for use by retail clients. While the information in this article has been prepared carefully, Brooks Macdonald gives no warranty as to the accuracy or completeness of the information.

The performance indicated for each sector should not be taken as an expectation of the future returns. Investors should be aware that the price of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and that neither is guaranteed. Past performance is not a reliable indicator for future returns. Investors may not get back the amount invested. Changes in rates of exchange may have an adverse effect on the value, price or income of an investment. Investors should be aware of the additional risks associated with funds investing in emerging or developing markets.

The information in this document does not constitute advice or a recommendation and you should not make any investment decisions on the basis of it. This document is for the information of the recipient only and should not be reproduced, copied or made available to others.

Sponsorship

Find out why leading brands in the private client industry are partnering with PCD to raise their profile, make connections and drive new business.

Membership

Find out how you can participate in the leading club for international private client advisors and unlock opportunities around the globe.